What Would We See if We Were Able to Travel Within the Multiverse?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/c4/dbc4cd8b-b4b3-4a28-b211-42bc49a87a11/42-46205410.jpg)

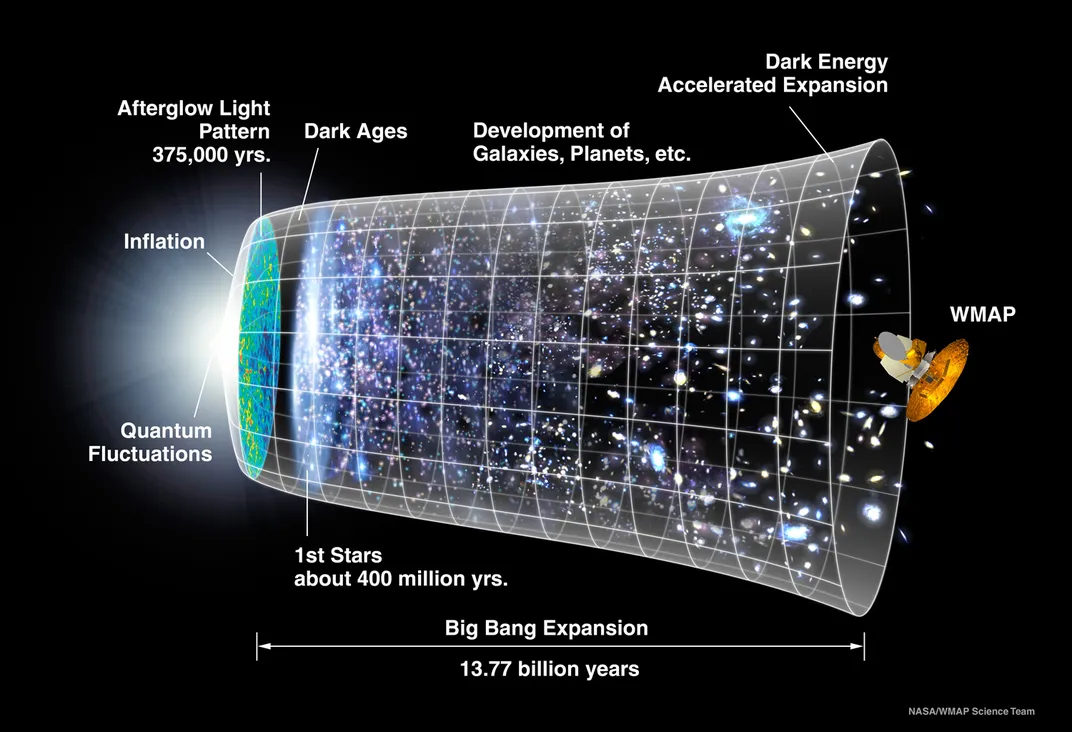

The universe began as a Big Bang and almost immediately began to expand faster than the speed of lite in a growth spurt called "inflation." This sudden stretching smoothed out the creation, smearing affair and radiation as across it like ketchup and mustard on a hamburger bun.

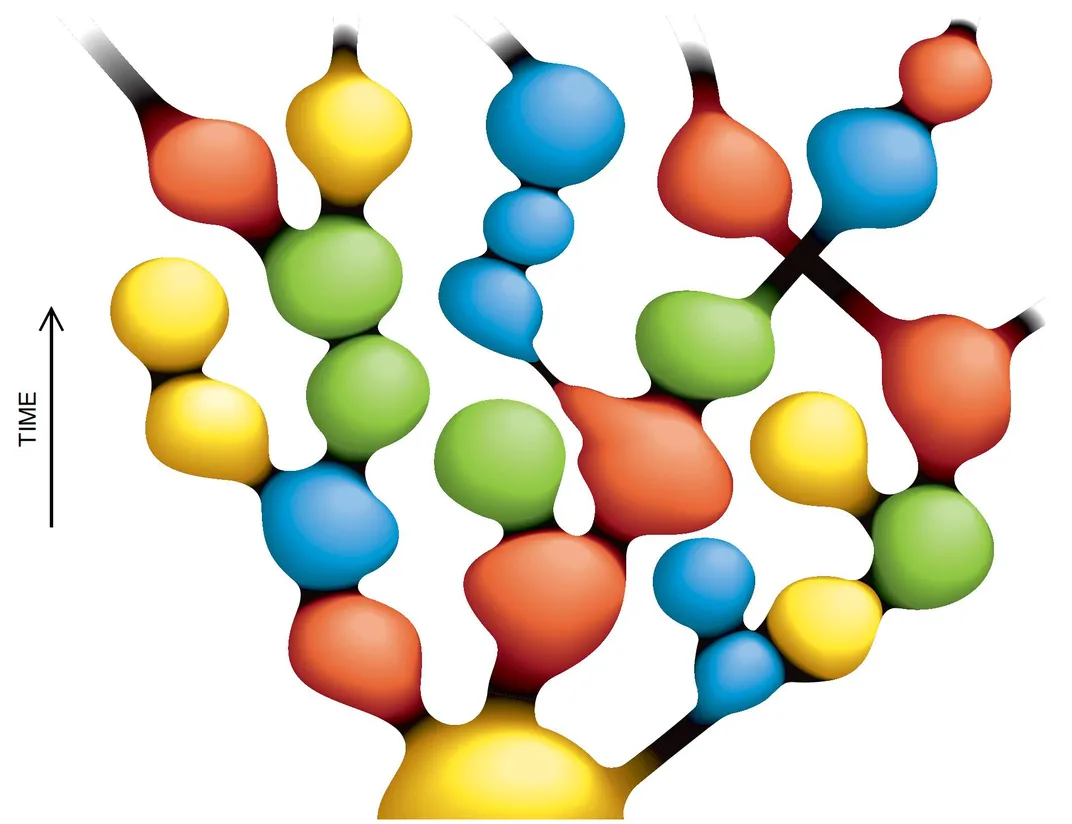

That expansion stopped afterward just a fraction of a second. But according to an idea called the "inflationary multiverse," it continues—simply not in our universe where we could come across it. And as it does, information technology spawns other universes. And even when it stops in those spaces, it continues in yet others. This "eternal inflation" would have created an infinite number of other universes.

Together, these cosmic islands form what scientists telephone call a "multiverse." On each of these islands, the physical fundamentals of that universe—like the charges and masses of electrons and protons and the mode space expands—could be different.

Cosmologists mostly study this inflationary version of the multiverse, but the foreign scenario can takes other forms, also. Imagine, for case, that the cosmos is infinite. Then the office of it that we can see—the visible universe—is just one of an uncountable number of other, same-sized universes that add to make a multiverse. Another version, called the "Many Worlds Interpretation," comes from quantum mechanics. Here, every time a physical particle, such as an electron, has multiple options, it takes all of them—each in a different, newly spawned universe.

But all of those other universes might exist beyond our scientific reach. A universe contains, by definition, all of the stuff anyone within can see, observe or probe. And because the multiverse is unreachable, physically and philosophically, astronomers may non be able to observe out—for sure—if it exists at all.

Determining whether or not nosotros live on i of many islands, though, isn't just a quest for pure cognition virtually the nature of the cosmos. If the multiverse exists, the life-hosting capability of our detail universe isn't such a mystery: An infinite number of less hospitable universes also be. The limerick of ours, then, would but be a happy coincidence. Just nosotros won't know that until scientists can validate the multiverse. And how they volition exercise that, and if it even possible to do that, remains an open up question.

Nothing results

This uncertainty presents a problem. In science, researchers try to explain how nature works using predictions that they formally call hypotheses. Colloquially, both they and the public sometimes call these ideas "theories." Scientists peculiarly gravitate toward this usage when their idea deals with a wide-ranging set of circumstances or explains something fundamental to how physics operates. And what could be more broad-ranging and fundamental than the multiverse?

For an idea to technically move from hypothesis to theory, though, scientists have to exam their predictions and then analyze the results to see whether their initial estimate is supported or disproved by the data. If the thought gains enough consistent support and describes nature accurately and reliably, it gets promoted to an official theory.

Every bit physicists spelunk deeper into the heart of reality, their hypotheses—like the multiverse—become harder and harder, and perchance even impossible, to test. Without the power to prove or disprove their ideas, at that place's no way for scientists to know how well a theory really represents reality. It's similar coming together a potential date on the net: While they may await skilful on digital paper, you tin't know if their contour represents their actual cocky until you lot meet in person. And if you never run across in person, they could be catfishing you. And so could the multiverse.

Physicists are now debating whether that trouble moves ideas similar the multiverse from physics to metaphysics, from the world of science to that of philosophy.

Show-me state

Some theoretical physicists say their field needs more common cold, difficult evidence and worry well-nigh where the lack of proof leads. "It is easy to write theories," says Carlo Rovelli of the Eye for Theoretical Physics in Luminy, France. Here, Rovelli is using the word colloquially, to talk about hypothetical explanations of how the universe, fundamentally, works. "Information technology is hard to write theories that survive the proof of reality," he continues. "Few survive. By means of this filter, we take been able to develop modern science, a technological society, to cure illness, to feed billions. All this works cheers to a simple idea: Do not trust your fancies. Keep only the ideas that can exist tested. If we terminate doing so, nosotros go back to the style of thinking of the Middle Ages."

He and cosmologists George Ellis of the University of Cape Boondocks and Joseph Silk of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore worry that because no ane can currently testify ideas like the multiverse right or wrong, scientists can only continue along their intellectual paths without knowing whether their walks are anything but random. "Theoretical physics risks becoming a no-man's-land betwixt mathematics, physics and philosophy that does non truly meet the requirements of any," Ellis and Silk noted in aNature editorial in December 2014.

It'due south not that physicists don't want to test their wildest ideas. Rovelli says that many of his colleagues idea that with the exponential advance of technology—and a lot of time sitting in rooms thinking—they would be able to validate them by now. "I call up that many physicists have not constitute a way of proving their theories, as they had hoped, and therefore they are gasping," says Rovelli.

"Physics advances in 2 manners," he says. Either physicists see something they don't understand and develop a new hypothesis to explicate it, or they expand on existing hypotheses that are in good working order. "Today many physicists are wasting time post-obit a third fashion: trying to estimate arbitrarily," says Rovelli. "This has never worked in the by and is not working now."

The multiverse might be i of those arbitrary guesses. Rovelli is not opposed to the thought itself simply to its purely cartoon-lath existence. "I see no reason for rejectinga priori the idea that there is more in nature than the portion of spacetime nosotros see," says Rovelli. "But I haven't seen whatsoever disarming bear witness so far."

"Proof" needs to evolve

Other scientists say that the definitions of "testify" and "proof" need an upgrade. Richard Dawid of the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy believes scientists could support their hypotheses, similar the multiverse—without actually finding concrete support. He laid out his ideas in a book chosenCord Theory and the Scientific Method. Inside is a kind of rubric, chosen "Not-Empirical Theory Assessment," that is like a science-fair judging sail for professional physicists. If a theory fulfills 3 criteria, it isprobably true.

First, if scientists have tried, and failed, to come up up with an culling theory that explains a miracle well, that counts equally evidence in favor of the original theory. Second, if a theory keeps seeming like a ameliorate idea the more yous written report it, that's another plus-one. And if a line of idea produced a theory that bear witness afterwards supported, chances are it volition again.

Radin Dardashti, likewise of the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy, thinks Dawid is straddling the right track. "The nearly bones idea undergirding all of this is that if nosotros have a theory that seems like it works, and we have come upwardly with nothing that works better, chances are our idea is correct," he says.

Only, historically, that undergirding has oft collapsed, and scientists haven't been able to meet the obvious alternatives to dogmatic ideas. For example, the Sunday, in its rising and setting, seems to go around World. People, therefore, long thought that our star orbited the Earth.

Dardashti cautions that scientists shouldn't become around applying Dawid'south idea willy-nilly, and that information technology needs more than evolution. Merely it may be the best idea out there for "testing" the multiverse and other ideas that are likewise hard, if non impossible, to test. He notes, though, that physicists' precious time would be improve spent dreaming up ways to find real testify.

Not everyone is then sanguine, though. Sabine Hossenfelder of the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics in Stockholm, thinks "post-empirical" and "science" can never live together. "Physics is not well-nigh finding Real Truth. Physics is about describing the world," she wrote on her blog Backreaction in response to an interview in which Dawid expounded on his ideas. And if an thought (which she also colloquially calls a theory) has no empirical, physical backing, it doesn't belong. "Without making contact to observation, a theory isn't useful to describe the natural world, not part of the natural sciences, and not physics," she concluded.

The truth is out in that location

Some supporters of the multiverse claim they have constitute existent physical evidence for the multiverse. Joseph Polchinski of the Academy of California, Santa Barbara, and Andrei Linde of Stanford Academy—some of the theoretical physicists who dreamed upwardly the current model of inflation and how information technology leads to island universes—say the proof is encoded in our cosmos.

This creation is huge, smooth and flat, just like inflation says it should be. "It took some time earlier we got used to the idea that the large size, flatness, isotropy and uniformity of the universe should non be dismissed as trivial facts of life," Linde wrote in a paper that appeared on arXiv.org in Dec. "Instead of that, they should be considered as experimental data requiring an caption, which was provided with the invention of inflation."

Similarly, our universe seems fine tuned to be favorable to life, with its Goldilocks expansion rate that'southward non too fast or too wearisome, an electron that'south not too big, a proton that has the exact opposite charge but the same mass every bit a neutron and a four-dimensional space in which nosotros can live. If the electron or proton were, for example, one percentage larger, beings could non be. What are the chances that all those properties would align to create a nice slice of real manor for biology to form and evolve?

In a universe that is, in fact, the only universe, the chances are vanishingly small. But in an eternally inflating multiverse, information technology is certain that one of the universes should turn out like ours. Each island universe can have different physical laws and fundamentals. Given infinite mutations, a universe on which humans can be born volition be built-in. The multiverse actually explains why we're hither. And our existence, therefore, helps explain why the multiverse is plausible.

These indirect pieces of prove, statistically combined, take led Polchinski to say he's 94 percent certain the multiverse exists. But he knows that's 5.999999 percent curt of the 99.999999 per centum sureness scientists need to call something a done bargain.

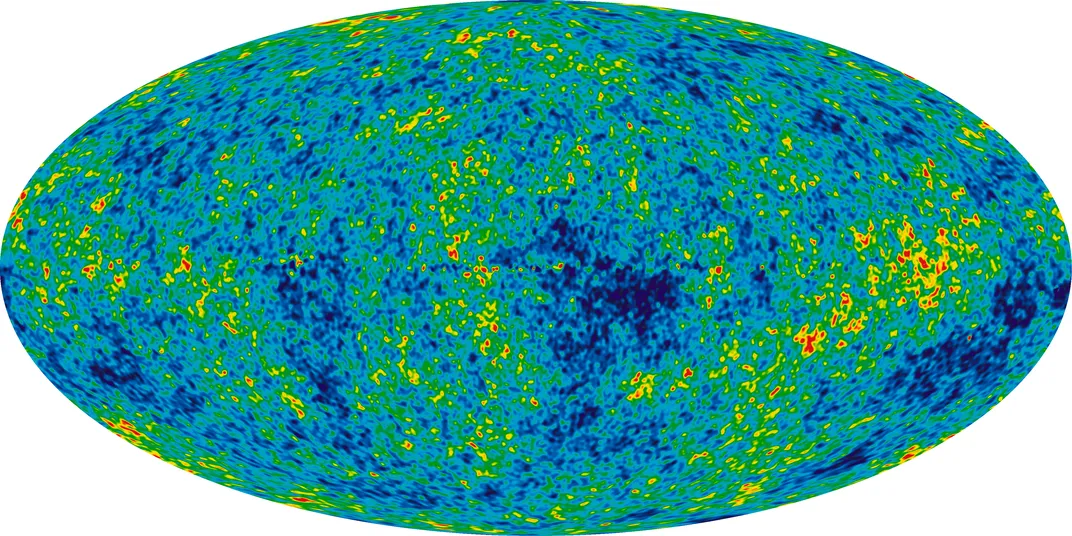

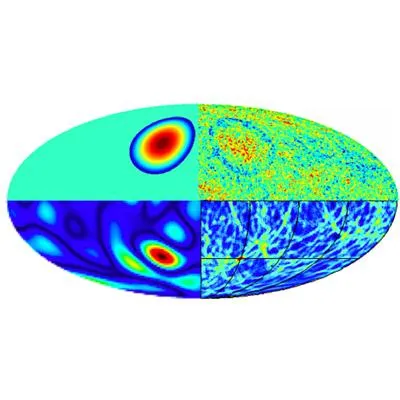

Eventually, scientists may exist able to discover more direct bear witness of the multiverse. They are hunting for the stretch marks that aggrandizement would take left on the cosmic microwave background, the light left over from the Large Bang. These imprints could tell scientists whether inflation happened, and aid them observe out whether it's still happening far from our view. And if our universe has bumped into others in the past, that fender-bender would too have left imprints in the cosmic microwave background. Scientists would be able to recognize that two-motorcar accident. And if two cars be, and then must many more.

Or, in fifty years, physicists may sheepishly present evidence that the early 21st-century's pet cosmological theory was wrong.

"Nosotros are working on a problem that is very hard, and so we should think nearly this on a very long time scale," Polchinski has brash other physicists. That's non unusual in physics. A hundred years ago, Einstein's theory of general relativity, for case, predicted the existence of gravitational waves. But scientists could only verify them recently with a billion-dollar instrument called LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

So far, all of scientific discipline has relied on testability. It has been what makes science science and not daydreaming. Its strict rules of proof moved humans out of dank, dark castles and into space. Simply those tests take time, and most theoreticians desire to wait it out. They are non ready to shelve an thought as key equally the multiverse—which could really exist the answer to life, the universe and everything—until and unless they can prove to themselves itdoesn't exist. And that day may never come up.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/can-physicists-ever-prove-multiverse-real-180958813/

0 Response to "What Would We See if We Were Able to Travel Within the Multiverse?"

Post a Comment